- Home

- Ray Bradbury

Killer, Come Back to Me Page 21

Killer, Come Back to Me Read online

Page 21

His eyes, as usual, instinctively, fastened upon the lady heading the table. Passing, he waved a finger near her cheek. She did not blink.

Aunt Rose sat firmly at the head of the table and if a mote of dust floated lightly down out of the ceiling spaces, did her eye trace its orbit? Did the eye revolve in its shellacked socket, with glassy cold precision? And if the dust mote happened upon the shell of her wet eye did the eye batten? Did the muscles clinch, the lashes close?

No.

Aunt Rose’s hand lay on the table like cutlery, rare and fine and old; tarnished. Her bosom was hidden in a salad of fluffy linen.

Beneath the table her stick legs in high-buttoned shoes went up into a pipe of dress. You felt that the legs terminated at the skirt line and from there on she was a department store dummy, all wax and nothingness responding, probably, with much the same chill waxen movements, with as much enthusiasm and response as a mannequin.

So here was Aunt Rose, staring straight at Greppin—he choked out a laugh and clapped hands derisively shut—there were the first hints of a dust mustache gathering across her upper lip!

“Good evening, Aunt Rose,” he said, bowing. “Good evening, Uncle Dimity,” he said, graciously. “No, not a word,” he held up his hand. “Not a word from any of you.” He bowed again. “Ah, good evening, cousin Lila, and you, cousin Sam.”

Lila sat upon his left, her hair like golden shavings from a tube of lathed brass. Sam, opposite her, told all directions with his hair.

They were both young, he fourteen, she sixteen. Uncle Dimity, their father (but “father” was a nasty word!) sat next to Lila, placed in this secondary niche long, long ago because Aunt Rose said the window draft might get his neck if he sat at the head of the table. Ah, Aunt Rose!

Mr. Greppin drew the chair under his tight-clothed little rump and put a casual elbow to the linen.

“I’ve something to say,” he said. “It’s very important. This has gone on for weeks now. It can’t go any further. I’m in love. Oh, but I’ve told you that long ago. On the day I made you all smile, remember?”

* * *

The eyes of the four seated people did not blink, the hands did not move.

Greppin became introspective. The day he had made them smile. Two weeks ago it was. He had come home, walked in, looked at them and said, “I’m to be married!”

They had all whirled with expressions as if someone had just smashed the window.

“You’re WHAT?” cried Aunt Rose.

“To Alice Jane Ballard!” he had said, stiffening somewhat.

“Congratulations,” said Uncle Dimity. “I guess,” he added, looking at his wife. He cleared his throat. “But isn’t it a little early, son?” He looked at his wife again. “Yes. Yes, I think it’s a little early. I wouldn’t advise it yet, not just yet, no.”

“The house is in a terrible way,” said Aunt Rose. “We won’t have it fixed for a year yet.”

“That’s what you said last year and the year before,” said Mr. Greppin. “And anyway,” he said bluntly, “this is my house.”

Aunt Rose’s jaw had clamped at that. “After all these years for us to be bodily thrown out, why I—”

“You won’t be thrown out, don’t be idiotic,” said Greppin, furiously.

“Now, Rose—” said Uncle Dimity in a pale tone.

Aunt Rose dropped her hands. “After all I’ve done—”

In that instant Greppin had known they would have to go, all of them. First he would make them silent, then he would make them smile, then, later, he would move them out like luggage. He couldn’t bring Alice Jane into a house full of grims such as these, where Aunt Rose followed you wherever you went even when she wasn’t following you, and the children performed indignities upon you at a glance from their maternal parent, and the father, no better than a third child, carefully rearranged his advice to you on being a bachelor. Greppin stared at them. It was their fault that his loving and living was all wrong. If he did something about them—then his warm bright dreams of soft bodies glowing with an anxious perspiration of love might become tangible and near. Then he would have the house all to himself and—and Alice Jane. Yes, Alice Jane.

They would have to go. Quickly. If he told them to go, as he had often done, twenty years might pass as Aunt Rose gathered sunbleached sachets and Edison phonographs. Long before then Alice Jane herself would be moved and gone.

Greppin looked at them as he picked up the carving knife.

* * *

Greppin’s head snapped with tiredness.

He flicked his eyes open. Eh? Oh, he had been drowsing, thinking.

All that had occurred two weeks ago. Two weeks ago this very night that conversation about marriage, moving, Alice Jane, had come about. Two weeks ago it had been. Two weeks ago he had made them smile.

Now, recovering from his reverie, he smiled around at the silent and motionless figures. They smiled back in peculiarly pleasing fashion.

“I hate you, old woman,” he said to Aunt Rose, directly. “Two weeks ago I wouldn’t have dared say that. Tonight, ah, well—” he lazed his voice, turning. “Uncle Dimity, let me give you a little advice, old man—”

He talked small talk, picked up a spoon, pretended to eat peaches from an empty dish. He had already eaten downtown in a tray cafeteria; pork, potatoes, apple pie, string beans, beets, potato salad. But now he made dessert-eating motions because he enjoyed this little act. He made as if he were chewing.

“So—tonight you are finally, once and for all, moving out. I’ve waited two weeks, thinking it all over. In a way I guess I’ve kept you here this long because I wanted to keep an eye on you. Once you’re gone, I can’t be sure—” And here his eyes gleamed with fear. “You might come prowling around, making noises at night, and I couldn’t stand that. I can’t ever have noises in this house, not even when Alice moves in.…”

The double carpet was thick and soundless underfoot, reassuring.

“Alice wants to move in day after tomorrow. We’re getting married.”

Aunt Rose winked evilly, doubtfully at him.

“Ah!” he cried, leaping up, then, staring, he sank down, mouth convulsing. He released the tension in him, laughing. “Oh, I see. It was a fly.” He watched the fly crawl with slow precision on the ivory cheek of Aunt Rose and dart away. Why did it have to pick that instant to make her eye appear to blink, to doubt. “Do you doubt I ever will marry, Aunt Rose? Do you think me incapable of marriage, of love and love’s duties? Do you think me immature, unable to cope with a woman and her ways of living? Do you think me a child, only daydreaming? Well!” He calmed himself with an effort, shaking his head. “Man, man,” he argued to himself. “It was only a fly, and does a fly make doubt of love, or did you make it into a fly and a wink? Damn it!” He pointed at the four of them.

“I’m going to fix the furnace hotter. In an hour I’ll be moving you out of the house once and for all. You comprehend? Good. I see you do.”

Outside, it was beginning to rain, a cold drizzling downpour that drenched the house. A look of irritation came to Greppin’s face. The sound of the rain was the one thing he couldn’t stop, couldn’t be helped. No way to buy new hinges or lubricants or hooks for that. You might tent the house-top with lengths of cloth to soften the sound, mightn’t you? That’s going a bit far. No. No way of preventing the rain sounds.

He wanted silence now, where he had never wanted it before in his life so much. Each sound was a fear. So each sound had to be muffled, gotten to and eliminated.

The drum of rain was like the knuckles of an impatient man on a surface. He lapsed again into remembering.

He remembered the rest of it. The rest of that hour on that day two weeks ago when he had made them smile.…

He had taken up the carving knife and prepared to cut the bird upon the table. As usual the family had been gathered, all wearing their solemn, puritanical masks. If the children smiled the smiles were stepped on like nasty bugs by Aunt Rose.

He had severed away much of it in some minutes before he slowly looked up at their solemn, critical faces, like puddings with agate eyes, and after staring at them a moment, as if discovered with a naked woman instead of a naked-limbed partridge, he lifted the knife and cried hoarsely, “Why in God’s name can’t you, any of you, ever smile? I’ll make you smile!”

He raised the knife a number of times like a magician’s wand.

And, in a short interval—behold! they were all of them smiling!

* * *

He broke that memory in half, crumpled it, balled it, tossed it down. Rising briskly, he went to the hall, down the hall to the kitchen, and from there down the dim stairs into the cellar where he opened the furnace door and built the fire steadily and expertly into wonderful flame.

Walking upstairs again he looked about him. He would have cleaners come and clean the empty house, redecorators slide down the dull drapes and hoist new shimmery banners up. New thick Oriental rugs purchased for the floors would subtly insure the silence he desired and would need at least for the next month, if not for the entire year.

He put his hands to his face. What if Alice Jane made noise moving about the house? Some noise, some how, some place!

And then he laughed. It was quite a joke. That problem was already solved. Yes, it was solved. He need fear no noise from Alice Jane. It was all absurdly simple. He would have all the pleasure of Alice Jane and none of the dream-destroying distractions and discomforts.

There was one other addition needed to the quality of silence. Upon the tops of the doors that the wind sucked shut with a bang at frequent intervals he would install air-compression brakes, those kind they have on library doors that hiss gently as their levers seal.

He passed through the dining room. The figures had not moved from their tableau. Their hands remained affixed in familiar positions, and their indifference to him was not impoliteness.

He climbed the hall stairs to change his clothing, preparatory to the task of moving the family. Taking the links from his fine cuffs, he swung his head to one side. Music. At first he paid it no mind. Then, slowly, his face swinging to the ceiling, the color drained out of his cheeks.

At the very apex of the house the music began, note by note, one note following another, and it terrified him.

Each note came like a plucking of one single harp thread. In the complete silence the small sound of it was made larger until it grew all out of proportion to itself, gone mad with all this soundlessness to stretch about in.

The door opened in an explosion from his hands, the next thing his feet were trying the stairs to the third level of the house, the banister twisted in a long polished snake under his tightening, relaxing, reaching-up, pulling hands! The steps went under to be replaced by longer, higher, darker steps. He had started the game at the bottom with a slow stumbling, now he was running with full impetus and if a wall had suddenly confronted him he would not have stopped for it until he saw blood on it and fingernail scratches where he tried to pass through.

He felt like a mouse running in a great clear space of a bell. And high in the bell sphere the one harp thread hummed. It drew him on, caught him up with an umbilical of sound, gave his fear sustenance and life, mothered him. Fears passed between mother and groping child. He sought to shear the connection with his hands, could not. He felt as if someone had given a heave on the cord, wriggling.

Another clear threaded tone. And another.

“No, keep quiet,” he shouted. “There can’t be noise in my house. Not since two weeks ago. I said there would be no more noise. So it can’t be—it’s impossible! Keep quiet!”

He burst upward into the attic.

Relief can be hysteria.

Teardrops fell from a vent in the roof and struck, shattering upon a tall neck of Swedish cut-glass flowerware with resonant tone.

He shattered the vase with one swift move of his triumphant foot!

* * *

Picking out and putting on an old shirt and old pair of pants in his room, he chuckled. The music was gone, the vent plugged, the silence again insured. There are silences and silences. Each with its own identity. There were summer night silences, which weren’t silences at all, but layer on layer of insect chorals and the sound of electric arc lamps swaying in lonely small orbits on lonely country roads, casting out feeble rings of illumination upon which the night fed—summer night silence which, to be a silence, demanded an indolence and a neglect and an indifference upon the part of the listener. Not a silence at all! And there was a winter silence, but it was an incoffined silence, ready to burst out at the first touch of spring, things had a compression, a not-for-long feel, the silence made a sound unto itself, the freezing was so complete it made chimes of everything or detonations of a single breath or word you spoke at midnight in the diamond air. No, it was not a silence worthy of the name. A silence between two lovers, when there need be no words. Color came in his cheeks, he shut his eyes. It was a most pleasant silence, a perfect silence with Alice Jane. He had seen to that. Everything was perfect.

Whispering.

He hoped the neighbors hadn’t heard him shrieking like a fool.

A faint whispering.

Now, about silences. The best silence was one conceived in every aspect by an individual, himself, so that there could be no bursting of crystal bonds, or electric-insect hummings, the human mind could cope with each sound, each emergency, until such a complete silence was achieved that one could hear one’s cells adjust in one’s hand.

A whispering.

He shook his head. There was no whispering. There could be none in his house. Sweat began to seep down his body, he began to shake in small, imperceptible shakings, his jaw loosened, his eyes were turned free in their sockets.

Whispering. Low rumors of talk.

“I tell you I’m getting married,” he said, weakly, loosely.

“You’re lying,” said the whispers.

His head fell forward on its neck as if hung, chin on chest.

“Her name is Alice Jane Ballard—” he mouthed it between soft, wet lips and the words were formless. One of his eyes began to jitter its lid up and down as if blinking out a message to some unseen guest. “You can’t stop me from loving her, I love her—”

Whispering.

He took a blind step forward.

The cuff of his pants leg quivered as he reached the floor grille of the ventilator. A hot rise of air followed his cuffs. Whispering.

The furnace.

* * *

He was on his way downstairs when someone knocked on the front door. He leaned against it. “Who is it?”

“Mr. Greppin?”

Greppin drew in his breath. “Yes?”

“Will you let us in, please?”

“Well, who is it?”

“The police,” said the man outside.

“What do you want, I’m just sitting down to supper!”

“Just want a talk with you. The neighbors phoned. Said they hadn’t seen your aunt and uncle for two weeks. Heard a noise awhile ago—”

“I assure you everything is all right.” He forced a laugh.

“Well, then,” continued the voice outside, “we can talk it over in friendly style if you’ll only open the door.”

“I’m sorry,” insisted Greppin. “I’m tired and hungry, come back tomorrow. I’ll talk to you then, if you want me to.”

“I’ll have to insist, Mr. Greppin.”

They began to beat against the door.

Greppin turned automatically, stiffly, walked down the hall past the old clock, into the dining room, without a word. He seated himself without looking at any one i

n particular and then he began to talk, slowly at first, then more rapidly.

“Some pests at the door. You’ll talk to them, won’t you, Aunt Rose? You’ll tell them to go away, won’t you, we’re eating dinner? Everyone else go on eating and look pleasant and they’ll go away, if they do come in. Aunt Rose you will talk to them, won’t you? And now that things are happening I have something to tell you.” A few hot tears fell for no reason. He looked at them as they soaked and spread in the white linen, vanishing. “I don’t know anyone named Alice Jane Ballard. I never knew anyone named Alice Jane Ballard. It was all—all—I don’t know. I said I loved her and wanted to marry her to get around somehow to make you smile. Yes, I said it because I planned to make you smile, that was the only reason. I’m never going to have a woman, I always knew for years I never would have. Will you please pass the potatoes, Aunt Rose?”

* * *

The front door splintered and fell. A heavy softened rushing filled the hall. Men broke into the dining room.

A hesitation.

The police inspector hastily removed his hat.

“Oh, I beg your pardon,” he apologized. “I didn’t mean to intrude upon your supper, I—”

The sudden halting of the police was such that their movement shook the room. The movement catapulted the bodies of Aunt Rose and Uncle Dimity straight away to the carpet, where they lay, their throats severed in a half moon from ear to ear— which caused them, like the children seated at the table, to have what was the horrid illusion of a smile under their chins, ragged smiles that welcomed in the late arrivals and told them everything with a simple grimace.…

The Fruit at the Bottom of the Bowl

William Acton rose to his feet. The clock on the mantel ticked midnight.

He looked at his fingers and he looked at the large room around him and he looked at the man lying on the floor. William Acton, whose fingers had stroked typewriter keys and made love and fried ham and eggs for early breakfasts, had now accomplished a murder with those same ten whorled fingers.

He had never thought of himself as a sculptor and yet, in this moment, looking down between his hands at the body upon the polished hardwood floor, he realized that by some sculptural clenching and remodeling and twisting of human clay he had taken hold of this man named Donald Huxley and changed his physiognomy, the very frame of his body.

Fahrenheit 451

Fahrenheit 451 Zen in the Art of Writing

Zen in the Art of Writing The Halloween Tree

The Halloween Tree The Stories of Ray Bradbury

The Stories of Ray Bradbury A Medicine for Melancholy and Other Stories

A Medicine for Melancholy and Other Stories S Is for Space

S Is for Space The Martian Chronicles

The Martian Chronicles Futuria Fantasia, Winter 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Winter 1940 Farewell Summer

Farewell Summer Something Wicked This Way Comes

Something Wicked This Way Comes R Is for Rocket

R Is for Rocket The Illustrated Man

The Illustrated Man The Golden Apples of the Sun

The Golden Apples of the Sun Dandelion Wine

Dandelion Wine The Cat's Pajamas

The Cat's Pajamas A Graveyard for Lunatics

A Graveyard for Lunatics The Playground

The Playground We'll Always Have Paris: Stories

We'll Always Have Paris: Stories Driving Blind

Driving Blind Let's All Kill Constance

Let's All Kill Constance The Day It Rained Forever

The Day It Rained Forever The Toynbee Convector

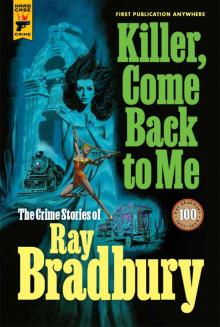

The Toynbee Convector Killer, Come Back to Me

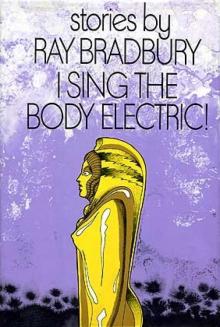

Killer, Come Back to Me I Sing the Body Electric

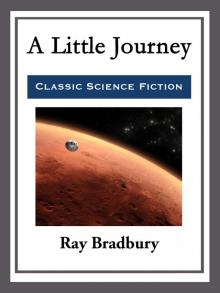

I Sing the Body Electric A Little Journey

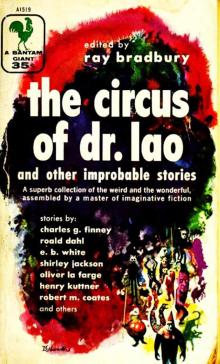

A Little Journey The Circus of Dr Lao and Other Improbable Stories

The Circus of Dr Lao and Other Improbable Stories Bradbury Stories: 100 of His Most Celebrated Tales

Bradbury Stories: 100 of His Most Celebrated Tales From the Dust Returned

From the Dust Returned Death Is a Lonely Business

Death Is a Lonely Business THE VELDT

THE VELDT One More for the Road

One More for the Road Futuria Fantasia, Summer 1939

Futuria Fantasia, Summer 1939 The Small Assassin

The Small Assassin Futuria Fantasia, Fall 1939

Futuria Fantasia, Fall 1939 Machineries of Joy

Machineries of Joy The October Country

The October Country A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories

A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories Quicker Than the Eye

Quicker Than the Eye Summer Morning, Summer Night

Summer Morning, Summer Night Yestermorrow

Yestermorrow Amazing Stories: Giant 35th Anniversary Issue (Amazing Stories Classics)

Amazing Stories: Giant 35th Anniversary Issue (Amazing Stories Classics) (1972) The Halloween Tree

(1972) The Halloween Tree Listen to the Echoes

Listen to the Echoes A Pleasure to Burn

A Pleasure to Burn Bradbury Stories

Bradbury Stories Bradbury Speaks

Bradbury Speaks Ray Bradbury Stories Volume 2

Ray Bradbury Stories Volume 2 Farewell Summer gt-2

Farewell Summer gt-2 The Lost Bradbury

The Lost Bradbury Green Shadows, White Whale

Green Shadows, White Whale Nine Rarities

Nine Rarities The Fireman

The Fireman Golden Aples of the Sun (golden aples of the sun)

Golden Aples of the Sun (golden aples of the sun) We'll Always Have Paris

We'll Always Have Paris The Machineries of Joy

The Machineries of Joy A Graveyard for Lunatics cm-2

A Graveyard for Lunatics cm-2 The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder Where Robot Mice and Robot Men Run Round In Robot Towns

Where Robot Mice and Robot Men Run Round In Robot Towns