- Home

- Ray Bradbury

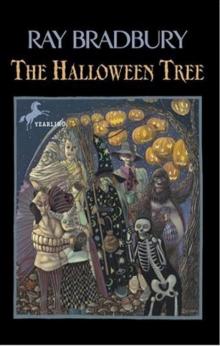

(1972) The Halloween Tree

(1972) The Halloween Tree Read online

The Halloween Tree

* * *

RAY BRADBURY

Illustrated by Joseph Mugnaini

THE HALLOWEEN TREE

A Bantam Spectra Book / published by arrangement with

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

PRINTING HISTORY

Knopf edition published June 1972

Bantam Edition / October 1974

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1994,1972 by Ray Bradbury.

Illustrations copyright © 1972 by Alfred A. Knopf

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part by mimeograph

or any other means, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

For information address: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

201 E. 50th Street, New York, NY 10022

* * *

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

With love for

MADAME MAN’HA GARREAU-DOMBASLE

met twenty-seven years

ago in the graveyard at

midnight on the Island

of Janitzio at Lake Patzcuaro,

Mexico, and remembered

on each anniversary of

The Day of the Dead.

A thousand pumpkin smiles look down from the Halloween Tree, and twice-times-a-thousand fresh-cut eyes glare and wink and blink, as Moundshroud leads the eight trick-or-treaters—no, nine. But where is Pipkin?—on a leaf-tossed, kite-flying, gliding, broomstick-riding trip to learn the secret of All Hallows’ Eve.

And they do.

“Well,” asks Moundshroud at journey’s end, “which was it? A Trick or a Treat?”

“Both!” all agree.

And so will you.

It was a small town by a small river and a small lake in a small northern part of a Midwest state. There wasn’t so much wilderness around you couldn’t see the town. But on the other hand there wasn’t so much town you couldn’t see and feel and touch and smell the wilderness. The town was full of trees. And dry grass and dead flowers now that autumn was here. And full of fences to walk on and sidewalks to skate on and a large ravine to tumble in and yell across. And the town was full of…

Boys.

And it was the afternoon of Halloween.

And all the houses shut against a cool wind.

And the town full of cold sunlight.

But suddenly, the day was gone.

Night came out from under each tree and spread.

Behind the doors of all the houses there was a scurry of mouse feet, muted cries, flickerings of light.

Behind one door, Tom Skelton, aged thirteen, stopped and listened.

The wind outside nested in each tree, prowled the sidewalks in invisible treads like unseen cats.

Tom Skelton shivered. Anyone could see that the wind was a special wind this night, and the darkness took on a special feel because it was All Hallows’ Eve. Everything seemed cut from soft black velvet or gold or orange velvet. Smoke panted up out of a thousand chimneys like the plumes of funeral parades. From kitchen windows drifted two pumpkin smells: gourds being cut, pies being baked.

The cries behind the locked house doors grew more exasperated as shadows of boys flew by windows. Half-dressed boys, greasepaint on their cheeks; here a hunchback, there a medium-sized giant. Attics were still being rummaged, old locks broken, old steamer chests disemboweled for costumes.

Tom Skelton put on his bones.

He grinned at the spinal cord, the ribcage, the kneecaps stitched white on black cotton.

Lucky! he thought. What a name you got! Tom Skelton. Great for Halloween! Everyone calls you Skeleton! So what do you wear?

Bones.

Wham. Eight front doors banged shut.

Eight boys made a series of beautiful leaps over flowerpots, rails, dead ferns, bushes, landing on their own dry-starched front lawns. Galloping, rushing, they seized a final sheet, adjusted a last mask, tugged at strange mushroom caps or wigs, shouting at the way the wind took them along, helped their running; glad of the wind, or cursing boy curses as masks fell off or hung sidewise or stuffed up their noses with a muslin smell like a dogs hot breath. Or just letting the sheer exhilaration of being alive and out on this night pull their lungs and shape their throats into a yell and a yell and a … yeeeellll!

Eight boys collided at one intersection.

“Here I am: Witch!”

“Apeman!”

“Skeleton!” said Tom, hilarious inside his bones.

“Gargoyle!”

“Beggar!”

“Mr. Death Himself!”

Bang! They shook back from their conclusions, all happy-fouled and tangled under a street-corner light. The swaying electric lamp belled in the wind like a cathedral bell. The bricks of the street became planks of a drunken ship all tilted and foundered with dark and light.

Behind each mask was a boy.

“Who’s that?” Tom Skelton pointed.

“Won’t tell. Secret!” cried the Witch, disguising his voice.

Everyone laughed.

“Who’s that?”

“Mummy!” cried the boy inside the ancient yellowed wrappings, like an immense cigar stalking the night streets.

“And who’s—?”

“No time!” said Someone Hidden Behind Yet Another Mystery of Muslin and Paint. “Trick or treat!”

“Yeah!”

Shrieking, wailing, full of banshee mirth they ran, on everything except sidewalks, going up into the air over bushes and down almost upon yipping dogs.

But in the middle of running, laughing, barking, suddenly, as if a great hand of night and wind and smelling-something-wrong stopped them, they stopped.

“Six, seven, eight.”

“That can’t be! Count again.”

“Four, five, six—”

“Should be nine of us! Someone’s missing!”

They sniffed each other, like fearful beasts.

“Pipkin’s not here!”

How did they know? They were all hidden behind masks. And yet, and yet…

They could feel his absence.

“Pipkin! He’s never missed a Halloween in a zillion years. Boy, this is awful. Come on!”

In one vast swerve, one doglike trot and ramble, they circled round and down the middle of the cobble-brick-street, blown like leaves before a storm.

“Here’s his place!”

They pulled to a halt. There was Pipkin’s house, but not enough pumpkins in the windows, not enough corn-shocks on the porch, not enough spooks peering out through the dark glass in the high upstairs tower room.

“Gosh,” said someone, “what if Pipkin’s sick?”

“It wouldn’t be Halloween without Pipkin”

“Not Halloween,” they moaned.

And someone threw a crabapple at Pipkin’s front door It made a small thump, like a rabbit kicking the wood.

They waited, sad for no reason, lost for no reason. They thought of Pipkin and a Halloween that might be a rotten pumpkin with a dead candle if, if, if—Pipkin wasn’t there.

Come on, Pipkin. Come out and save the Night!

Why were they waiting, afraid for one small boy?

Because…

Joe Pipkin was the greatest boy who ever lived. The grandest boy who ever fell out of a tree and laughed at the joke. The finest boy who ever raced around the track, winning, and then, seeing his friends a mile back somewhere, stumbled and fell, waited for them to catch up, and joined, breast and breast, breaking the winner’s tape. The jolliest boy who ever hunted out all the haunted houses in town, which are hard to find, and came back to report on them and take all the kids to ramble through the basements and scramble up the ivy outside-bricks and sh

out down the chimneys and make water off the roofs, hooting and chimpanzee-dancing and ape-bellowing. The day Joe Pipkin was born all the Orange Crush and Nehi soda bottles in the world fizzed over; and joyful bees swarmed countrysides to sting maiden ladies. On his birthdays, the lake pulled out from the shore in midsummer and ran back with a tidal wave of boys, a big leap of bodies and a downcrash of laughs.

Dawns, lying in bed, you heard a birdpeck at the window. Pipkin.

You stuck your head out into the snow-water-clear-summer-morning air.

There in the dew on the lawn rabbit prints showed where, just a moment ago, not a dozen rabbits but one rabbit had circled and crisscrossed in a glory of life and exultation, bounding hedges, clipping ferns, tromping clover. It resembled the switchyards down at the rail depot. A million tracks in the grass but no …

Pipkin.

And here he rose up like a wild sunflower in the garden. His great round face burned with fresh sun. His eyes flashed Morse code signals:

“Hurry up! It’s almost over!”

“What?”

“Today! Now! Six A.M.! Dive down! Wade in it!”

Or: “This summer! Before you know, bang!—it’s gone! Quick!”

And he sank away in sunflowers to come up all onions.

Pipkin, oh, dear Pipkin, finest and loveliest of boys.

How he ran so fast no one knew. His tennis shoes were ancient. They were colored green of forests jogged through, brown from old harvest trudges through September a year back, tar-stained from sprints along the docks and beaches where the coal barges came in, yellow from careless dogs, splinter-filled from climbing wood fences. His clothes were scarecrow clothes, worn by Pipkin’s dogs all night, loaned to them for strolls through town, with chew marks along the cuffs and fall marks on the seat.

His hair? His hair was a great hedgehog bristle of bright brown-blond daggers sticking in all directions. His ears, pure peachfuzz. His hands, mittened with dust and the good smell of airedales and peppermint and stolen peaches from the far country orchards.

Pipkin. An assemblage of speeds, smells, textures; a cross section of all the boys who ever ran, fell, got up, and ran again.

No one, in all the years, had ever seen him sitting still. He was hard to remember in school, in one seat, for one hour. He was the last into the schoolhouse and the first exploded out when the bell ended the day.

Pipkin, sweet Pipkin.

Who yodeled and played the kazoo and hated girls more than all the other boys in the gang combined.

Pipkin, whose arm around your shoulder, and secret whisper of great doings this day, protected you from the world.

Pipkin.

God got up early just to see Pipkin come out of his house, like one of those people on a weatherclock. And the weather was always fine where Pipkin was.

Pipkin.

They stood in front of his house.

Any moment now that door would open wide. Pipkin would jump out in a blast of fire and smoke. And Halloween would REALLY begin! Come on, Joe, oh, Pipkin, they whispered, come on!

The front door opened.

Pipkin stepped out.

Not flew. Not banged. Not exploded.

Stepped out.

And came down the walk to meet his friends.

Not running. And not wearing a mask! No mask!

But moving along like an old man, almost.

“Pipkin!” they shouted, to scare away their uneasiness.

“Hi, gang,” said Pipkin.

His face was pale. He tried to smile, but his eyes looked funny. He was holding his right side with one hand as if he had a boil there.

They all looked at his hand. He took his hand away from his side.

“Well,” he said with faint enthusiasm. “We ready to go?”

“Yeah, but you don’t look ready,” said Tom. “You sick?”

“On Halloween?” said Pipkin. “You kidding?”

“Where’s your costume—?”

“You go on ahead, I’ll catch up.”

“No, Pipkin, we’ll wait for you to—”

“Go on,” said Pipkin, saying it slowly, his face deathly pale now. His hand was back on his side.

“You got a stomachache?” asked Tom. “You told your folks?”

“No, no, I can’t! They’d—” Tears burst from Pipkin’s eyes. “It’s nothing, I tell you. Look. Go straight on toward the ravine. Head for the House, okay? The place of the Haunts, yeah? Meet you there.”

“You swear?”

“Swear. Wait’ll you see my costume!”

The boys began to back off. On the way, they touched his elbow, or knocked him gently in the chest, or ran their knuckles along his chin in a fake fight. “Okay, Pipkin. As long as you’re sure—”

“I’m sure.” He took his hand away from his side. His face colored for a moment as if the pain were gone. “On your marks. Get set. Go!”

When Joe Pipkin said “Go,” they Went.

They ran.

They ran backward halfway down the block, so they could see Pipkin standing there, waving at them.

“Hurry up, Pipkin!”

“I’ll catch you!” he shouted, a long way off.

The night swallowed him.

They ran. When they looked back again, he was gone.

They banged doors, they shouted Trick or Treat and their brown paper bags began to fill with incredible sweets. They galloped with their teeth glued shut with pink gum. They ran with red wax lips bedazzling their faces.

But all the people who met them at doors looked like candy factory duplicates of their own mothers and fathers. It was like never leaving home. Too much kindness flashed from every window and every portal. What they wanted was to hear dragons belch in basements and banged castle doors.

And so, still looking back for Pipkin, they reached the edge of town and the place where civilization fell away in darkness.

The Ravine.

The ravine, filled with varieties of night sounds, lurkings of black-ink stream and creek, lingerings of autumns that rolled over in fire and bronze and died a thousand years ago. From this deep place sprang mushroom and toadstool and cold stone frog and crawdad and spider. There was a long tunnel down there under the earth in which poisoned waters dripped and the echoes never ceased calling Come Come Come and if you do you’ll stay forever, forever, drip, forever, rustle, run, rush, whisper, and never go, never go go go …

The boys lined up on the rim of darkness, looking down.

And then Tom Skelton, cold in his bones, whistled his breath in his teeth like the wind blowing over the bedroom screen at night. He pointed.

“Oh, hey—that’s where Pipkin told us to go!”

He vanished.

All looked. They saw his small shape race down the dirt path into one hundred million tons of night all crammed in that huge dark pit, that dank cellar, that deliciously frightening ravine.

Yelling, they plunged after.

Where they had been was empty.

The town was left behind to suffer itself with sweetness.

They ran down through the ravine at a swift rush, all laughing, jostling, all elbows and ankles, all steamy snort and roustabout, to stop in collision when Tom Skelton stopped and pointed up the path.

“There,” he whispered. “There’s the only house in town worth visiting on Halloween! There!”

“Yeah!” said everyone.

For it was true. The house was special and fine and tall and dark. There must have been a thousand windows in its sides, all shimmering with cold stars. It looked as if it had been cut out of black marble instead of built out of timbers, and inside? who could guess how many rooms, halls, breezeways, attics. Superior and inferior attics, some higher than others, some more filled with dust and webs and ancient leaves or gold buried above ground in the sky but lost away so high no ladder in town could take you there.

The house beckoned with its towers, invited with its gummed-shut doors. Pirate ships are a tonic. Ancient fort

s are a boon. But a house, a haunted house, on All Hallows’ Eve? Eight small hearts beat up an absolute storm of glory and approbation.

“Come on.”

But they were already crowding up the path. Until they stood at last by a crumbling wall, looking up and up and still farther up at the great tombyard top of the old house. For that’s what it seemed. The high mountain peak of the mansion was littered with what looked like black bones or iron rods, and enough chimneys to choke out smoke signals from three dozen fires on sooty hearths hidden far below in the dim bowels of this monster place. With so many chimneys, the roof seemed a vast cemetery, each chimney signifying the burial place of some old god of fire or enchantress of steam, smoke, and firefly spark. Even as they watched, a kind of bleak exhalation of soot breathed up out of some four dozen flues, darkening the sky still more, and putting out some few stars.

“Boy,” said Tom Skelton, “Pipkin sure knows what he’s talking about!”

“Boy,” said all, agreeing.

They crept along a weed-infested path toward the crumpled front porch.

Tom Skelton, alone, itched his bony foot up on the first porch-step. The others gasped at his bravery. So, now, finally in a mob, a compact mass of sweating boys moved up on the porch amid fierce cries of the planks underfoot, and shudderings of their bodies. Each wished to pull back, swivel about, run, but found himself trapped against the boy behind or in front or to the side. So, with a pseudo-pod thrust out here or there, the amoebic form, the large perspiration of boys leaned and made a run and a stop to the front door of the house which was as tall as a coffin and twice as thin.

They stood there for a long moment, various hands reaching out like the legs of an immense spider as if to twist that cold knob or reach up for the knocker on that front door. Meanwhile, the wooden floorings of the porch sank and wallowed beneath their weight, threatening at every shift of proportion to give way and fling them into some cockroach abyss beneath. The planks, each tuned to an A or an F or a C, sang out their uncanny music as heavy shoes scraped on them. And if there had been time and it were noon, they might have danced out a cadavers tune or a skeleton’s rigadoon, for who can resist an ancient porch which, like a gigantic xylophone, only wants to be jumped on to make music?

Fahrenheit 451

Fahrenheit 451 Zen in the Art of Writing

Zen in the Art of Writing The Halloween Tree

The Halloween Tree The Stories of Ray Bradbury

The Stories of Ray Bradbury A Medicine for Melancholy and Other Stories

A Medicine for Melancholy and Other Stories S Is for Space

S Is for Space The Martian Chronicles

The Martian Chronicles Futuria Fantasia, Winter 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Winter 1940 Farewell Summer

Farewell Summer Something Wicked This Way Comes

Something Wicked This Way Comes R Is for Rocket

R Is for Rocket The Illustrated Man

The Illustrated Man The Golden Apples of the Sun

The Golden Apples of the Sun Dandelion Wine

Dandelion Wine The Cat's Pajamas

The Cat's Pajamas A Graveyard for Lunatics

A Graveyard for Lunatics The Playground

The Playground We'll Always Have Paris: Stories

We'll Always Have Paris: Stories Driving Blind

Driving Blind Let's All Kill Constance

Let's All Kill Constance The Day It Rained Forever

The Day It Rained Forever The Toynbee Convector

The Toynbee Convector Killer, Come Back to Me

Killer, Come Back to Me I Sing the Body Electric

I Sing the Body Electric A Little Journey

A Little Journey The Circus of Dr Lao and Other Improbable Stories

The Circus of Dr Lao and Other Improbable Stories Bradbury Stories: 100 of His Most Celebrated Tales

Bradbury Stories: 100 of His Most Celebrated Tales From the Dust Returned

From the Dust Returned Death Is a Lonely Business

Death Is a Lonely Business THE VELDT

THE VELDT One More for the Road

One More for the Road Futuria Fantasia, Summer 1939

Futuria Fantasia, Summer 1939 The Small Assassin

The Small Assassin Futuria Fantasia, Fall 1939

Futuria Fantasia, Fall 1939 Machineries of Joy

Machineries of Joy The October Country

The October Country A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories

A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories Quicker Than the Eye

Quicker Than the Eye Summer Morning, Summer Night

Summer Morning, Summer Night Yestermorrow

Yestermorrow Amazing Stories: Giant 35th Anniversary Issue (Amazing Stories Classics)

Amazing Stories: Giant 35th Anniversary Issue (Amazing Stories Classics) (1972) The Halloween Tree

(1972) The Halloween Tree Listen to the Echoes

Listen to the Echoes A Pleasure to Burn

A Pleasure to Burn Bradbury Stories

Bradbury Stories Bradbury Speaks

Bradbury Speaks Ray Bradbury Stories Volume 2

Ray Bradbury Stories Volume 2 Farewell Summer gt-2

Farewell Summer gt-2 The Lost Bradbury

The Lost Bradbury Green Shadows, White Whale

Green Shadows, White Whale Nine Rarities

Nine Rarities The Fireman

The Fireman Golden Aples of the Sun (golden aples of the sun)

Golden Aples of the Sun (golden aples of the sun) We'll Always Have Paris

We'll Always Have Paris The Machineries of Joy

The Machineries of Joy A Graveyard for Lunatics cm-2

A Graveyard for Lunatics cm-2 The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder Where Robot Mice and Robot Men Run Round In Robot Towns

Where Robot Mice and Robot Men Run Round In Robot Towns